We Wont Grow Old Together

Get your frogs legs and croissants at the ready and prepare for a conflict of culture you English pig-dogs! If you don't know anything about the country that invented cinema, I fart in your general direction. The French have been making films since the dawn of time, wielding their paintbrushes in the air and creating patterns of random delight across their celluloid. The world became aware of the petite red, white and blue country during the late 1950s and early 1960s when the film movement Nouvelle Vague (French New Wave) exploded in our faces with Francois Truffaut's 400 Blows (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960). Since the glory days between 1958 and 1964, France has been at the forefront of world cinema, challenging and subverting our Hollywood induced brains with fragmented editing techniques, un-classical story structure, cinematic surrealism, captivating character development, hand-held cameras and a departure from the wrapped in plastic endings that we are used too.

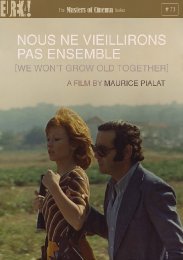

The rebellious filmmaker that took French Cinema by storm after the fuss over the New Wave subsided was the misanthropic Maurice Pialat. His dark brooding visions of reality are more akin to British social realist filmmakers like Ken Loach (Kes [1969]), Mike Leigh (Meantime [1984]) and Shane Meadows (This is England [2006]). By dealing with realistic and turbulent issues like foster care, cancer, physical and mental abuse, working class criminals, promiscuous teenagers, abortion, corruption, religion and mental illness, he defined his own veritable 'Cinema Verite' visions rather than absorbing the intellectual middle-class existentialism of the Cahiers du Cinema clan. Pialat's film career began at the age of 43 in 1967 with the grim drama L'Enfance Nue [Naked Childhood] that put the spotlight on the turbulent life of a 10-year-old boy forced into foster care. Under their Masters of Cinema label, Eureka Entertainment are proud to announce the DVD release of Pialat's second film Nous Ne Vieillirons Pas Ensemble [We Will Not Grow Old Together], a story whose heartbeat comes directly from Pialat's own turbulent experiences of a relationship that became plagued by verbal outbursts of violence.

Jean is a documentary filmmaker. Even though he has a loving wife of eleven-years, something is missing. Spending time with the youthful redhead Catherine, they idle away their time on the beach, drive around Paris and stay in hotel rooms. However, their relationship is not as wonderful as it seems. Jean becomes verbally abusive, 'I'm ruining my life by being with you'. While on holiday, he accuses Catherine of cheating. To make up for it he proposes to her. Catherine refuses the offer and finally makes a decision to end the liaison to develop a 'real' relationship and get married. As soon as they split up, they get back together. However, things soon become sour again. Refusing to have sex in a hotel room, Jean jerks Catherine back and forth. She decides to take a break to think about life. Will Catherine decide to get married and live a happy secure life away from the self-destructive relationship with Jean?

If you've ever lived in a broken relationship, you will appreciate the subtle sentiment and nuance of We Wont Grow Old Together. The film begins with Jean and Catherine in bed. Catherine ponders their tenuous relationship. There is no love between them anymore, 'It's dead…there's just no life'. Jean is disinterested in the conversation and turns over to get some sleep. In the next scene, Jean is making coffee in the kitchen as Catherine walks in with the noise of her hairdryer pounding like a hover over the empty soundtrack. It creates an immediate anxiety. The camera takes on a mind of its own, clinically observing the characters in a hand-held documentary style that probes their problematic relationship. We are intrusive voyeurs, hiding in the shadows, watching the carnage of their gradual frustration with each other. It's like being a witness to a car accident; we morbidly observe the bloodbath, unable to look away, compelled to watch. Their relationship is a directionless cycle of love and hate that is going nowhere. Its one of the greatest break up movies committed to celluloid.

Jean is a womaniser. He treats Catherine with disrespect and disregard with his possessiveness and jealousy, giving her the impression that he doesn't really care for her anymore. His emotional abuse is harrowing. As they sit together in a car, after Jean has visited his wife, he insults her by calling her spineless, lazy, ugly, vulgar and ordinary. It's a traumatic experience for the audience as Catherine just sits there taking it all in with tears brewing in her eyes. In addition, it is done in one seamless shot. Jean tells her to clear off and storms out of the car, locks the doors and disappears, leaving Catherine waiting by the car in the cold. She looks around sheepishly, not knowing what to do or where to go. When Jean strolls back, Catherine is still waiting. There is a genuine moment of regret as he touches her hand and declares, 'your hands are freezing'. Catherine has no self-respect or self-confidence to say anything.

Jean has genuine emotions for Catherine but has a strange way of showing it. One of the few scenes in the movie in which the couple are liberated from their torment is when Jean picks Catherine up from the train station. The couple go swimming in the ocean. They flail around in the water, jesting about taking off their clothes, kissing each other in a tender manner while feeling the force of the waves against their skin. Wrapped in the fantasy of nature these two characters are free from their anxieties. There is a sympathetic quality to Jean, even though he is a complete bastard there's something endearing about him. He's real. He's the type of person that doesn't appreciate what he has until he loses it. Why do people fall in love only to fall out of love? Filmmakers have explored this problematic theme since the creation of cinema.

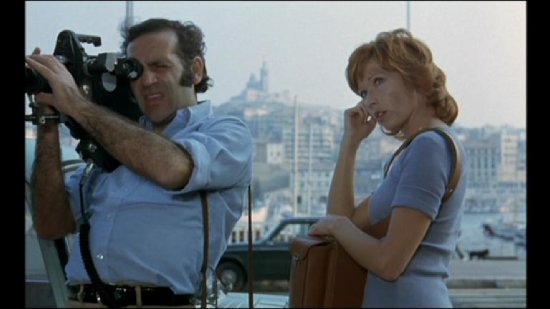

The cinema verite look to the film is rough, raw and down in the dirt. The cinematography is hidden in the naturalism of everyday life. As Jean is filming random shots in the market for his documentary, a women picks up her crying son and looks at the camera, an old lady is almost knocked over, a local man (who is obviously not involved in the film) bellows at Jean for the way he is treating Catherine. Keeping in character, the actor Jean Yanne, tells him to 'p.i.s.s. off'. The film has an emotional nakedness with a raw organic nature that over-stylised films can't reproduce. This is realism at its best. However, there is a high level of stylised proficiency in the film that doesn't go unnoticed. When Jean picks Catherine up from a café in his car, the camera operator is sitting in the backseat with his hand-held camera. As the car stops, the camera zooms in on Catherine sitting on a red chair. As she walks towards the car, the camera zooms back to its original shot. It's an interesting scene as we see the back of Jean, his face in the rear-view mirror and Catherine walking towards the car. It's disorientating as they drive off as we are subjected to the same bumps and turns as the characters.

Even though the subject matter is about a break up there are touching scenes of intimacy at the heart of this movie. The director, Maurice Pialat, pours his soul into the film by injecting scenes with real life experiences of his own disastrous relationship. Pialat is a master at making his audience feel uncomfortable by connecting us to our own personal experiences of loss. Jean is a realistic character that reflects Pialat's own awkward personality. There is a naked honesty in every breathe that Jean Yanne takes. He's not acting the part, he is the part.

Pialat directed ten films in his lifetime. His career spanned four decades. He died in 2003 at the age of 77.

"Pialat is dead and we are all orphaned"

(Gilles Jacob, Cannes president)

"I started too old, and finished too young."

(Maurice Pialat)

Special Features

• A 19-minute 2003 video interview with star Marlène Jobert about the film, conducted by Serge Toubiana (former editor-in-chief of Cahiers du cinéma and director of the Cinémathèque Française).

• La Camargue (1966) - A short 6-minute essay-documentary by Maurice Pialat on the region in which much of the action of Nous ne vieillirons pas ensemble unfolds.

• A 5-minute excerpt from the 1972 "Pour le cinéma: Spécial Cannes", featuring interviews with Jean Yanne and Maurice Pialat, both at Cannes, and two scenes deleted from the final film.

• An 8-minute excerpt from the 1972 program "Vive le cinéma", featuring François Truffaut in conversation about both Nous ne vieillirons pas ensemble and Pialat's earlier L'Enfance-nue, and including two unedited printed takes from the main feature.

• A 12-minute excerpt from another 1972 installment of "Vive le cinéma", featuring Maurice Pialat in conversation about the film.

• Original trailer for the film, and trailers for the six other Maurice Pialat features available from The Masters of Cinema Series.

• A lengthy booklet with a new essay by critic, publisher, and former Cahiers du cinéma editor-in-chief Emmanual Burdeau, and newly translated interviews with Maurice Pialat.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!